How to define autism and why it matters

I've centered my life around nerds for decades. Many of them sit in a room full of other awkward nerds, feeling secretly out of place like they don't belong, & somehow assume they're the only one who is secretly uncomfortable.

The term "neurotypical" experienced meaning-drift, until it became worse than useless, just like the word "planet". It needs ontological remodeling.

I've centered my life around nerds for decades. Many of them sit in a room full of other awkward nerds, feeling secretly out of place like they don't belong, & somehow assume they're the only one who is secretly uncomfortable.

The term "neurotypical" experienced meaning-drift, until it became worse than useless, just like the word "planet". It needs ontological remodeling.

There's a lot of equivocation on this. So let's define terms. "Neurotypical" means "not neurodivergent".

One way to find out what neurodivergent means is to ask the coiner of the term. PSA From The Actual Coiner Of Neurodivergent

Don't tell me "but neurotypical only means the opposite of my condition". Neurotypical is defined as not neurodivergent, and neurodivergent is a thousand ways to diverge. So, neurotypical means people who have no differences, no conditions. Somehow identical brains? Not diverse? As if that's possible???

"But that's an absurd definition. Sophisticated people don't use neurotypical to mean identical clones who are all perfect." At this point you're acting as the motte in the two-party motte-and-bailey, a bait-and-switch rhetorical tactic. Sometimes it's not one person switching between Motte and Bailey. Sometimes it's at least two; one as the Motte (the bait), and the other as the Bailey (the switch).

1. Bailey people will start off saying "Santa is literally real".

2. Next, I disagree.

3. Motte people say "But Santa is real in our hearts". This creates a taboo in the group against denying Santa.

4. The Bailey people start back on their shit about Santa being literal.

5. Now there's a norm in the group, of literal Santa.

Another way to find out what "neurotypical" has come to mean is to look at the top of the search results. The bailey is a fantasy of a world full of brains which, supposedly, are naturally healthy and effortlessly effective.

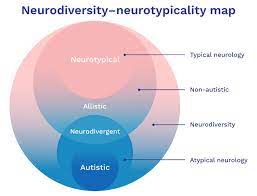

Look at this Venn diagram (also from the top of Google search results) which may as well be a one-dimensional spectrum. The reality is multi-dimensional.

In all the most predominant examples of definitions of "neurodivergent", that concept is defined against something. While your attention is focused on someone being different, an unspoken assumption sneaks in behind your back. The assumption goes like this: "there is a vast majority of humans who are not different, not struggling, & life comes easy to them." "Neurotypicals".

Early in life we often think we're going through unique problems. When we "fake it to make it", we aware that we're doing that, because we have an inside view of ourselves. We can't read others' minds, so we have a fantasy of their advantages. (And by the way, if you can't read minds, that doesn't make you autistic. No one else can read minds either, even though they think they can and they tell you that you should.)

We don't realize until later in life that everyone else was faking it too. It's like horoscopes; a description that applies to everybody which is mistaken for a unique description of one's specialness. Scott Alexander has a blog post explaining that in detail, as it applies to self-diagnosis.

So we get this myth, "social success comes easily to other people without working on themselves. My dissatisfaction with myself is intrinsic, permanent, unchangeable." And now, there are paid professionals to help you keep that attitude throughout adulthood.

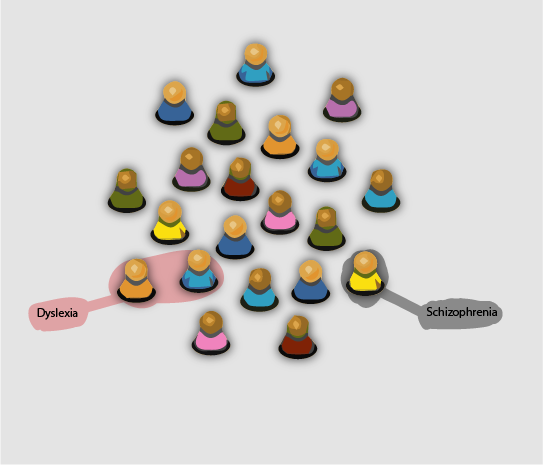

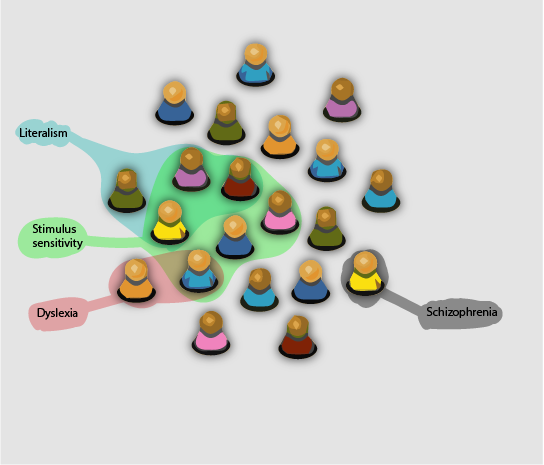

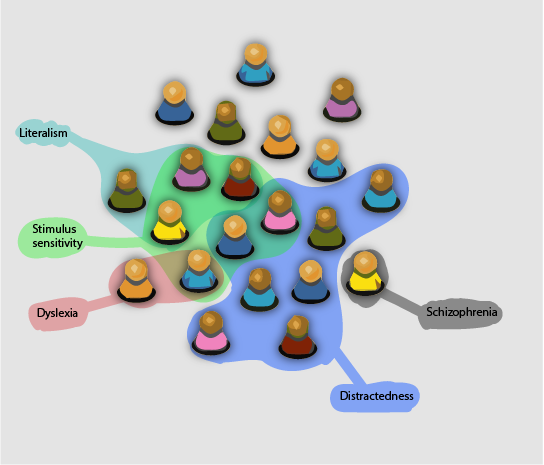

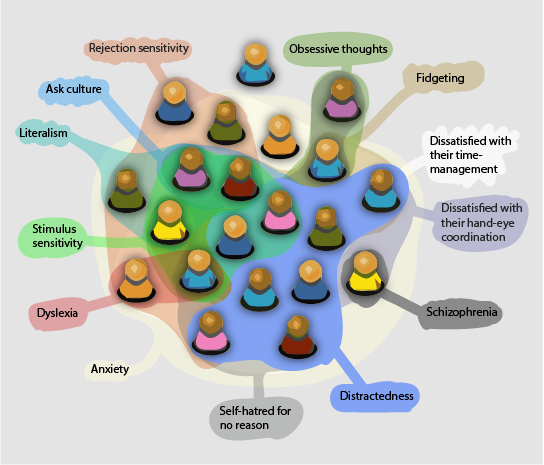

I made these graphics (populations not to scale) to show the ontology of a supposed "neurotypical majority" gradually collapsing into incoherence.

Now notice there's only one person left with no labels. Is this the only person in the world who's in the majority?

Of course if you divide up that graphic according to one condition at a time, everyone is in at least one majority. But in a world where everyone's brain diverges, "those whose brains diverge" is not a minority.

I agree, you are different! Because we're all different. You're different but not special. If everyone's special, no one is. Not everything you feel makes you special.

I agree, you are different! Because we're all different. You're different but not special. If everyone's special, no one is. Not everything you feel makes you special.

The word "neurotypical" doesn't work as a term of art, even as a professional definition. The best way around the problems I've described is to specify a condition and attach "non" to the front of it to indicate those who don't have that condition. Say "non-autists", "non-schizophrenics", "non-ADHD", or whatever the scientific or medical paper you're writing is about. Be specific.

What's At Stake

Duncan Sabien has an article titled Social Dark Matter, in which he makes the point that there are many more people with autism than you think; and indeed, many more of everything than you think.

Let me rephrase that: there are many more people with the label "autism" than you think. Take any given label. You and I define it narrowly enough for it to be useful, and as we narrow the definition, fewer people fit it. But for any such given label, it can be defined so broadly as to be useless or even counterproductive. And then there are many, many more than you thought.

Duncan Sabien, coming from the rationalist community, prioritizes epistemology (how to evaluate truth claims, such as through research) and sometimes misses ontology ("counting as"). Within a primarily-or-only-epistemological frame, there are not multiple definitions for words, and so there is one simple clear-cut question, "is this person autistic or not?" Then you just do poorly-designed studies, and count how many people self-diagnosed or got their doctor to give them a diagnosis, and get a number. That approach doesn't ask ontological questions, like

Let me rephrase that: there are many more people with the label "autism" than you think. Take any given label. You and I define it narrowly enough for it to be useful, and as we narrow the definition, fewer people fit it. But for any such given label, it can be defined so broadly as to be useless or even counterproductive. And then there are many, many more than you thought.

Duncan Sabien, coming from the rationalist community, prioritizes epistemology (how to evaluate truth claims, such as through research) and sometimes misses ontology ("counting as"). Within a primarily-or-only-epistemological frame, there are not multiple definitions for words, and so there is one simple clear-cut question, "is this person autistic or not?" Then you just do poorly-designed studies, and count how many people self-diagnosed or got their doctor to give them a diagnosis, and get a number. That approach doesn't ask ontological questions, like

- in what sense

- to what degree

- by what diagnostic criteria

- for what purposes

And so, Duncan assumes your lower number was wrong. But you weren't wrong. Words are tools. You were defining a word narrowly enough to be useful for something. I need to know whether you are asking me to keep the noise down around you. Whether a weighted blanket is an appropriate gift for me to give you. How much to use non-literal figures of speech. Not all symptoms are the same! Don't treat neurodivergence like it's all the same and comes as a package deal!

This misunderstanding is at its most painful in his section IV: The Law Of Extremity. He identifies many different extents to which one can "be autistic", but never says what those at all the different extents have in common. If they have something in common other than a label, he doesn't mention it. But that's skipping a crucial ontological step!

This misunderstanding is at its most painful in his section IV: The Law Of Extremity. He identifies many different extents to which one can "be autistic", but never says what those at all the different extents have in common. If they have something in common other than a label, he doesn't mention it. But that's skipping a crucial ontological step!

- Does it include self-diagnosis?

- Does it include doctors giving out diagnoses because the patient asked them to persistently enough?

- Does it include diagnostic criteria getting broader by the year?

- Is it a list of traits that are just ... near-universals of the human condition?

- Do you just check off the majority of a list of diagnostic criteria, like "takes things too literally", "cuts the tags off their shirts because they can't ignore them", "fidgets a lot", "needs a weighted blanket to sleep", "feels socially awkward sometimes", and assume they share an underlying etiology?

Maybe, maybe not, but it seems like a crux! The thing they all have in common could have something to do with predictive processing: "an unusually high reliance on bottom-up rather than top-down information, leading to weak central coherence and constant surprisal as the sensory data fails to fall within pathologically narrow confidence intervals." That would be great! That's what I'm asking for. But I've only ever read that in one article, despite it being needed in hundreds of articles that equivocate about autism!

You might wonder why it matters if we switch between a broad definition and one of several narrow definitions without noticing. Writer Freddie DeBoer lists some problems:

- Normalizing disability inevitably centers the most normal and sidelines the most severely afflicted.

- Once disability becomes identity, treating disability as something bad becomes forbidden.

- Disability is trivialized by these social practices.

- Refusing to frame disability as something negative makes the concept of reasonable accommodation incoherent.

I once lived in a group house with a problem roommate. On the one hand, she has invisible mental and emotional disabilities, so we should pay her bills and do her chores while she smokes weed and plays World Of Warcraft. But on the other hand, when making decisions as a house, we should consider that her thinking and emotions are disabled, and her perceptions and decisions are going to be poorer for it. This is especially true when we consider how strongly to take the bursts of anger she releases at all of us on a regular basis. We need to give her a pass because she's impaired and not functioning well. But that doesn't work for her, because it's important to her that she be taken seriously. So, all of a sudden, she no longer considers autism, ADHD, trauma, and other diagnoses to be impairments. She considers them a beautiful harmless quirky identity, which gives her a better perspective than neurotypicals, a word she employs like a slur. In both cases, she gets what she wants, and her housemates don't. But these two definitions are contradictory. This was a case of one person playing both sides of a motte-and-bailey.

My home was not the only big thing in my life, that I cared about deeply, that was sunk by this pattern. Not even close.

My home was not the only big thing in my life, that I cared about deeply, that was sunk by this pattern. Not even close.

Duncan Sabien is capable of speaking, reading, dressing himself, and using restrooms without assistance, and does not suddenly screech for no perceptible reason. He is ambitious, capable, in the upper echelons, describing himself with the label "autism". Does he use it to heavily imply he should get a pass on our social expectations of him, whenever our reasonable expectations are inconvenient? Should he not need to grow as a person, on the idea that the ways he lets other people down are intrinsic and permanent? Only those in his life can say, I suppose. All you and I can see from our vantage point is that it improves his social positioning. Freddie DeBoer has another article on this: The Gentrification of Disability.

Words are tools, and in ontological remodeling, whether a word is good or ruined depends on how it can be used. Someone I know and love has children in their teens, who will never, ever, ever, move out or provide for themselves, because of autism. You know how people complain about being exhausted in the first year or two of parenting? That is her life, caring for her teenagers moment-to-moment, into their adulthood, forever. I need a word that keeps that meaning. I need to say that word and have people jump to attention and provide care as if I cried "wolf" and there was an actual wolf.

You are not autistic. We need a different word for "feels socially awkward sometimes".

no subject

Date: 2024-05-23 10:07 pm (UTC)I understand the desire to name the thing that's going on, though, and to want very badly to be able to say it's not just one's own personal failure. I still remember the *enormous* relief when I got a medical diagnosis for why I was having functional problems in my mid-twenties after losing two jobs in short succession, that didn't just boil down to "I'm a fat lazy loser." I was putting so much on myself for not being a better person and for failing at things, it was making it hard to cope at all. Knowing it wasn't just a personal failing made it more possible to cope, pick myself up, and hunt for yet another job, and keep that one for a reasonable amount of time (still a lot of churn in IT).

Of course, that diagnosis didn't fix some really bad habits I'd picked up along the way. A diagnosis can't fix everything, even when prescription medication will help with the original/root cause.

Link fix for Not Everything You Feel Makes You Special: https://freddiedeboer.substack.com/you-dont-have-adhd-feelings-you-just (t on the end)

Link fix for Law of Extremity: https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/KpMNqA5BiCRozCwM3/social-dark-matter#VI__The_Law_of_Extremity

no subject

Date: 2024-05-23 10:26 pm (UTC)